Oxford movement

Oxford University’s Centre for the Humanities, funded with a gift of £185 million from Stephen Schwarzman, founder of Blackstone, and designed by Hopkins, is an optimistic harbinger of the future of cultural production, consumption, study and the whole panoply of the humanities as an intellectual field, writes Jeremy Melvin.

It fulfils the university’s long held ambition to build specialist teaching facilities for humanities – a lecturer in the theology department was apparently promised a new building on being appointed in 1972, and 30 years later, when William Whyte was appointed to the history faculty, he was made the same promise. Whyte is now professor of architectural and social history when not occupied as the university’s ‘senior responsible owner’ (ie the client co-ordinator, to translate Oxford-speak) for the Schwarzman Centre.

The project history is not just long but also convoluted. The 4ha former Radcliffe Infirmary site was earmarked for redevelopment some time ago, with a masterplan and building by Rafael Vinoly (named for Andrew Wiles, the mathematician who proved Fermat’s last theorem), Herzog & de Meuron’s £75 million Blavatnik Centre for Government (a decade ago), and a range for Somerville College (where Mrs Gandhi and Mrs Thatcher both studied) by Niall Mclaughlin. The Blavatnik is a floating glass oval, while Mclaughlin’s building is recognizably within the tradition of Oxford architecture of the last generation, of which Richard MacCormac was probably the progenitor and almost certainly the most consummate practitioner, heavily articulated and richly detailed and finished.

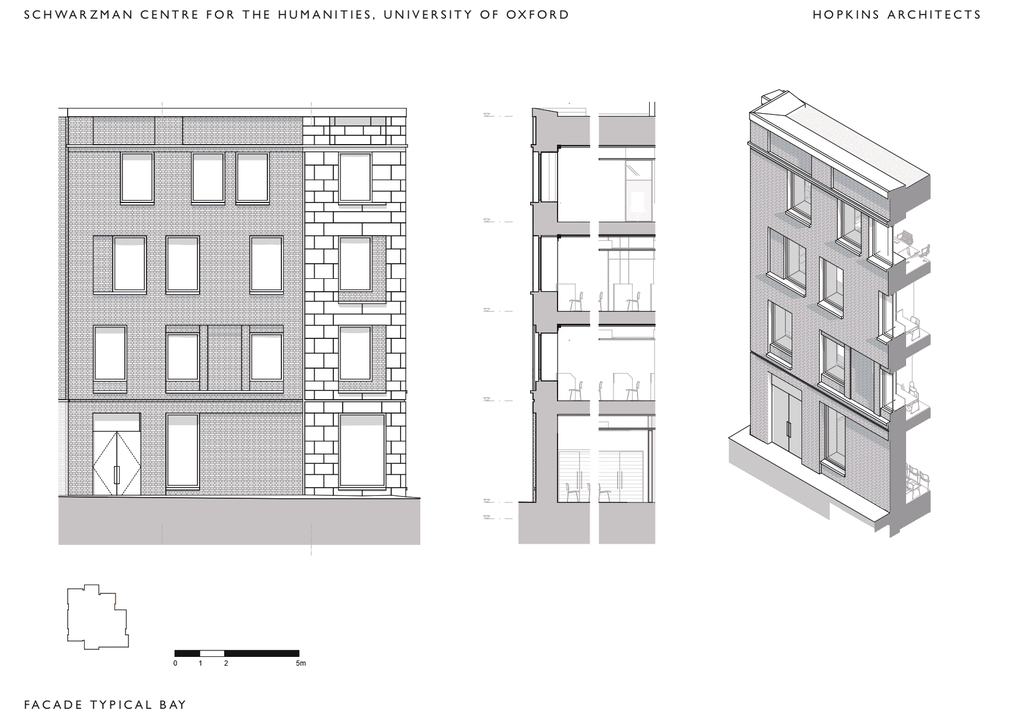

Typical bay: the building was constructed to Passivhaus standards (the first concert hall to achieve this), requiring very thick walls for insulation, air tightness and large ducts to move air.

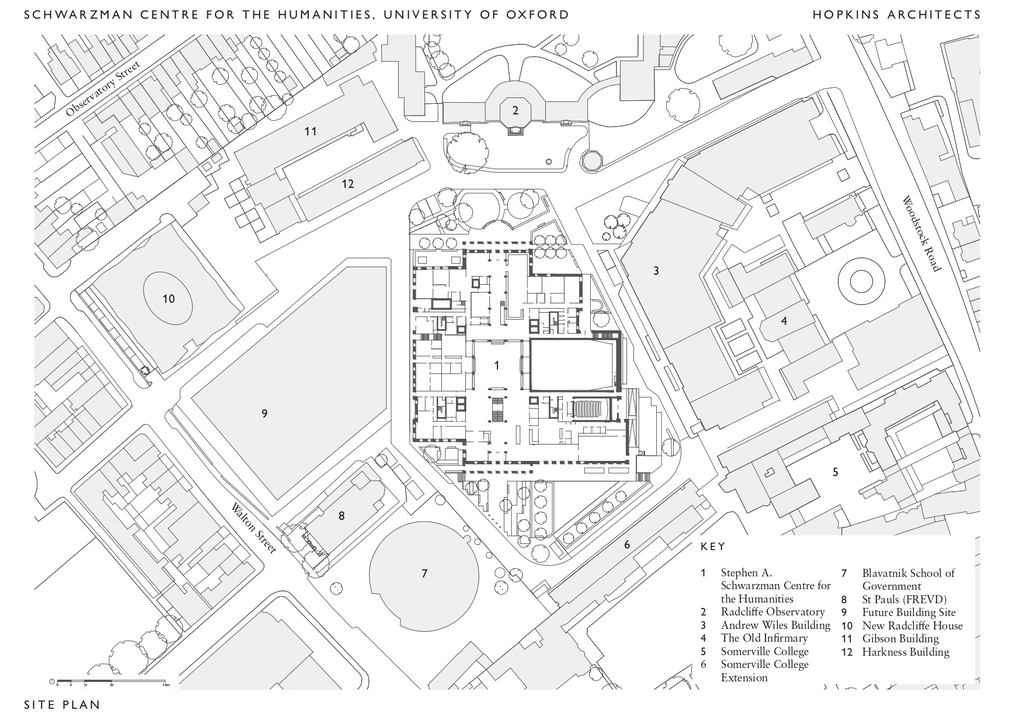

The site, in the Jericho area, includes the former paupers’ burial ground and lies just outside Oxford’s historic centre, but its influence is still very present. Just across the road is the grandiose neo-classical Oxford University Press, while on the other side of the Schwarzman is James Wyatt’s fine Radcliffe Observatory (not to be confused with either the hospital, now located in a 1970s YRM building in Headington, or James Gibbs’ Radcliffe Camera).

So the site has history (archaeological investigation showed traces of habitation from 5000 years ago) and good buildings among its neighbours, and despite strict height limits, plenty of possibilities for a fine addition. It took Schwarzman’s donation, announced in June 2019, to kickstart the project. Hopkins were selected through a competition and appointed just before the pandemic struck – Whyte and Hopkins director Andy Barnett remember carrying out the early design stages over Teams.

Schwarzman’s donation was conditional on creating more than just a teaching facility for humanities. He was keen to ensure public access and amenity, which drove the brief and design. It was to include a range of performance spaces, a public route through the building, centred on a grand inner hall under a dome, together with programmes designed to enrich cultural life for the public as well as academics and students.

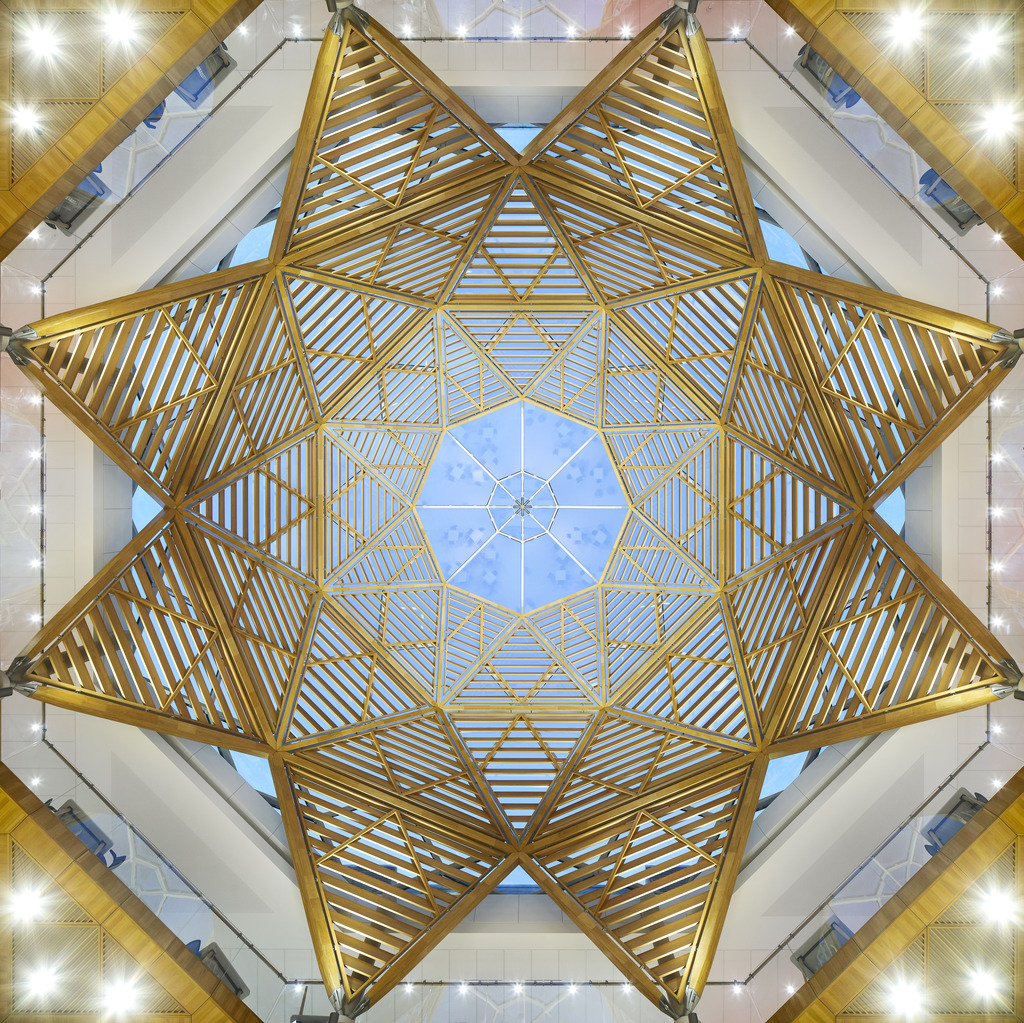

View of the dome in the Great

Hall, Stephen A. Schwarzman

Centre for the Humanities,

University of Oxford. Photograph

© Hufton + Crow

One of the project’s significant achievements is to initiate a synergic relationship between public and academic interests. Oxford does not have a performing arts department and many of the famous musicians among its alumni did not study music, but there are plenty of student societies for drama and talented musicians studying other subjects. The Schwarzman Centre offers opportunities for them. It has a theatre which can hold up to 250 people, through easily reconfigurable to a thrust stage or in the round. Its size also serves the intention of being unintimidating for young performers who might lack confidence but offers experience that may build it. There is also a black box, with a sprung floor for dance and powerful sound and projection facilities so it can simulate almost any visual or audio environment.

View of the theatre, Stephen A.

Schwarzman Centre for the

Humanities, University of Oxford.

Photograph © Hufton + Crow

As well as offering opportunities for performers, this facility will also provide training in the technical skills increasingly needed for contemporary performance. Alongside these are a small recital room – home to the university’s gamelan – and the performing centrepiece, a 500-seat concert hall. There is also a 100-seat cinema, and a white box for installations.

View of the Sohmen Concert Hall,

Stephen A. Schwarzman Centre for

the Humanities, University of

Oxford. Photograph © Hufton +

Crow

The concert hall is masterful. Finished largely in timber with red seats, similar to those at Hopkins’ Glyndebourne, it is full of subtle detailing which ensures fine acoustic performance: fabric drapes can drop from recesses above the wall panels to increase dampening, depending on the desired effect. Two rows of seats in the stalls can be removed, and the floor dropped to create an orchestra pit for semi-staged opera performances. Behind the stage which can hold up to 50 musicians, the balcony widens from one row of seats to give space for a choir. So it can host a wide range of musical concerts, but like all the performance spaces, can be used for lectures as well.

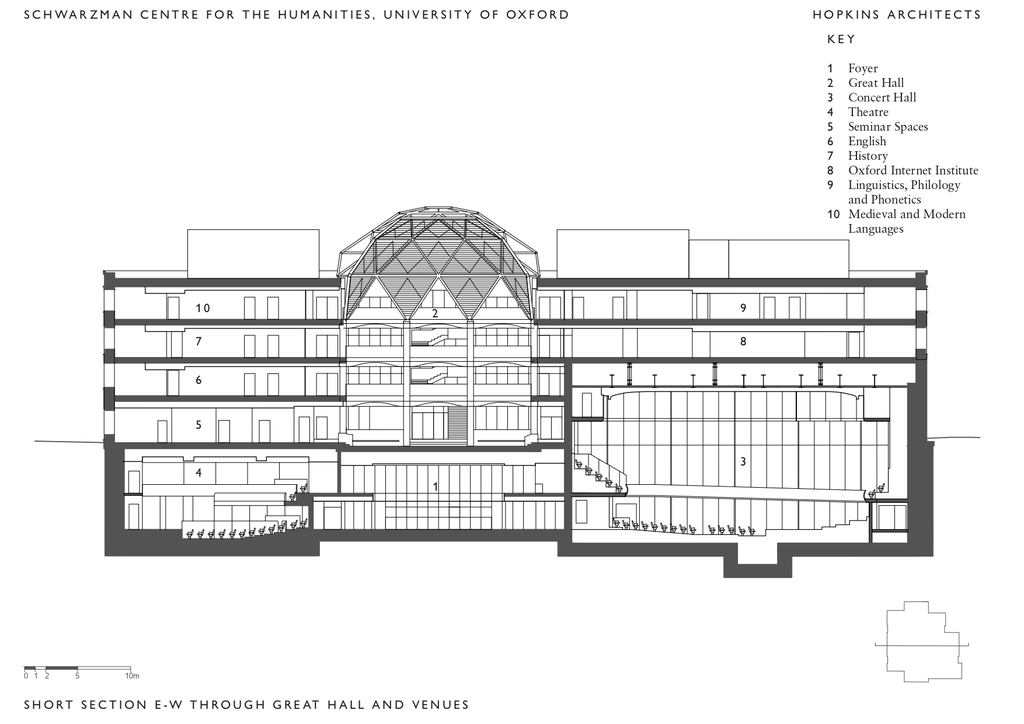

The architectural challenge was to fit these large and shape-specific volumes with formidable acoustic requirements, plus an imperative to work towards the university’s goal of net zero, into a single building. This had to include the faculties of English, history, mediaeval and modern languages, linguistics philology and phonetics, music, theology and religion, and philosophy, alongside the Institute for Ethics in AI, and the Oxford Internet Institute, as well as six libraries and the Bate Collection of musical instruments. Oxford still teaches through tutorials, typically pairs of students in conversation with one tutor, so there is a demand for a lot of small rooms including for music practice, as well as the set piece spaces, resulting around 1,000 rooms across the building.

Short section, showing how the large volumes fit

Hopkins’ design resolves these challenges elegantly and attractively. Both main public entrances, to the north and south are approached through arcades built, as are the facades from Clipsham stone which has a warm feel and an appealing grain. They form either end of the public route through the building, with the Bate Collection adjacent to the north entrance (and accessible through a separate route for school groups). The foyers are open and inviting, from the south at least clearly indicating the location of the performance spaces, which is necessarily at the second basement level (though the theatre and concert hall balconies can be reached from the first basement), due to their volumetric needs and the city-imposed height restrictions. Easy way-finding was an important goal, as the building is intended to attract local parents with prams or push chairs, as well as visiting academic and performers.

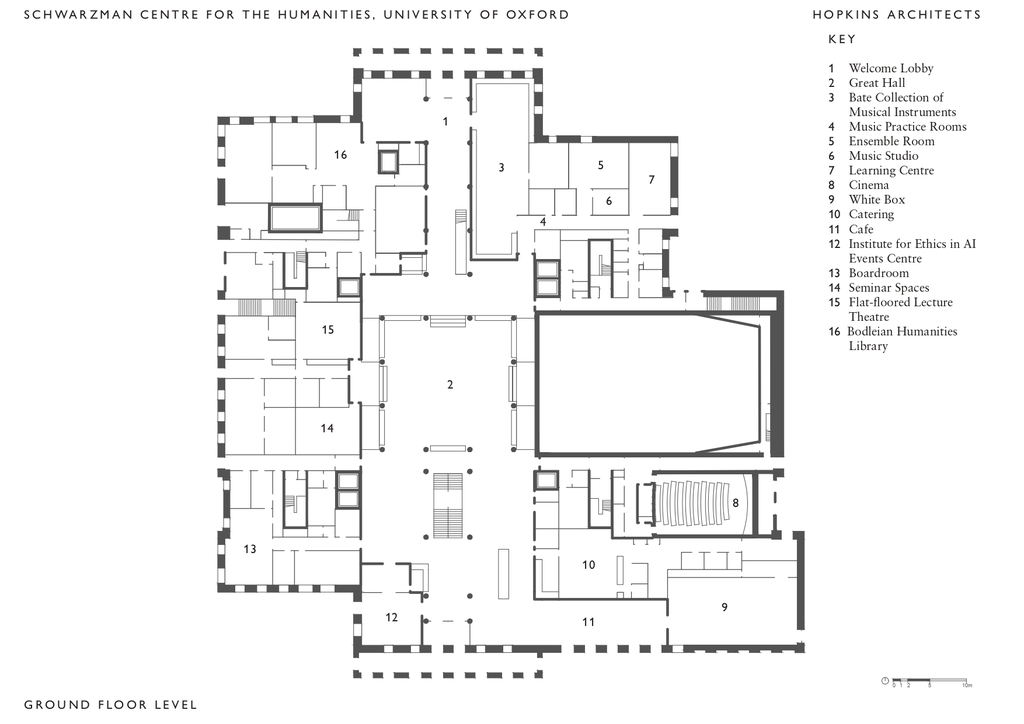

Ground floor plan

All is centred around a large and attractive four-storey atrium surmounted by a double dome, the inner of timber and the outer glass and steel, termed the Great Hall. Generally an open meeting space, with groups of seats for informal conversations or consumption of the rather fine fair from the café, it can also double as a performance space, with an audience spread across the galleries. There is even provision for stage backdrops. The ground level has the cinema and white box, one level up is the English department, with history, philology etc and languages above. Theology, as Whyte puts it, is ‘closer to God’ on the top floor. There is also a roof terrace with views to, you guessed it, the city’s dreaming spires. Libraries are close to their departmental offices, and all have access to informal seating areas on the galleries. The predominant material throughout the great hall is stone, with plenty of timber (English oak) and fabric covered seats following a subtle shift in colour for each floor.

View of the Great Hall, Stephen

A. Schwarzman Centre for the

Humanities, University of Oxford.

Photograph © Hufton + Crow

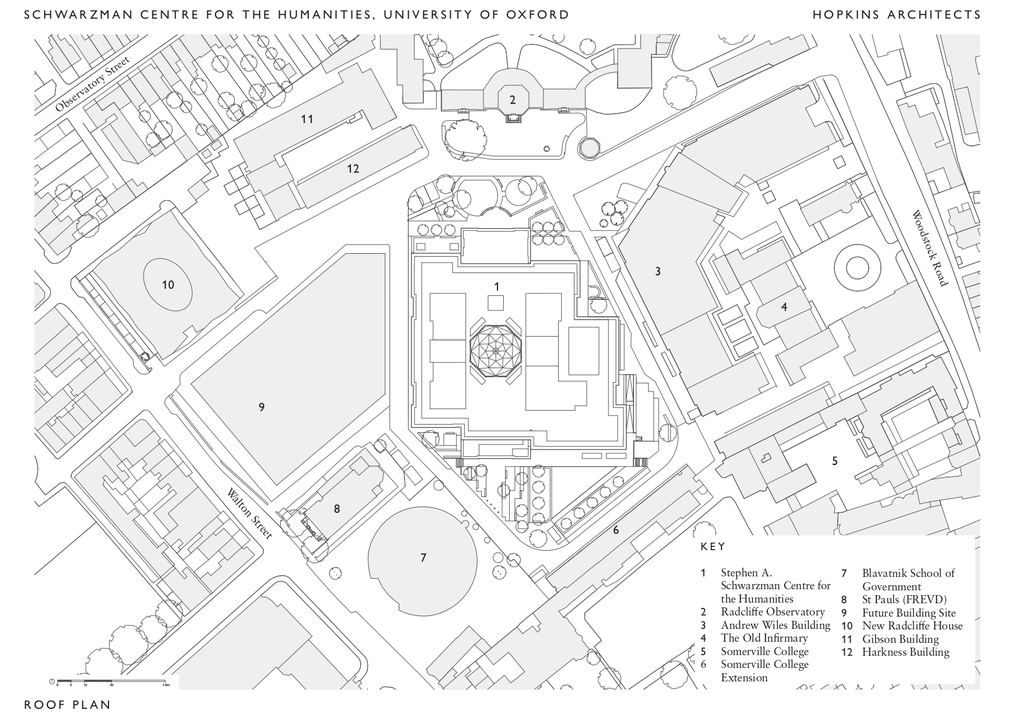

Roof plan

The hall is vital to the programme as well as the architectural impression. It is a contemporary interpretation of the traditional Oxbridge quadrangle, through with more inviting entrances and less forbidding gatekeepers, or the famous Renaissance courtyard of the university’s Bodleian library, with the original ‘schools’ arranged around it. In this sense it stands for and encourages interaction between ideas and ways of thinking, as well as collaboration between people with different practices – all fundamental to the project’s ethos.

Interaction is promoted in several ways. Obviously the public will be encouraged to buy tickets for events once the programme starts next April, but a key initiative is to appoint cultural fellows, distinguished creatives who primarily are not academics but performers and practitioners. The first wave includes composer Anna Clyne, choreographer Wayne MacGregor, sitar player Anoushka Shankar, artist Es Devlin and curator Hans Ulrich Obrist. The idea is that they interact with students, whether pursuing academic or personal work, and with academics.

So not only does the architecture look back to the origins of university buildings, but the programme rediscovers the original essence and purpose of the university – to cover the universal range of human intellectual activity and to develop it through interaction and collaboration with other disciplines and practitioners. Schwarzman has made many other donations to academic institutions, but was particularly keen to make an impact on the humanities, and went to what he believed was the foremost university in that field in the world, Oxford, despite having no previous connection to it. He is an alumnus of and donor to Yale; other recipients of his largesse include Johns Hopkins and MIT. But his inspired philanthropy (this project would never have received public funding) and Hopkins’ design, have enabled Oxford to inaugurate a new path to developing the humanities, as a universal human experience, fortified by serious academic research and creative endeavour.

Founder Partner