First Nations in focus

Few locations offer more to a city than the site of Cape Town, writes Jeremy Melvin. It has a superb natural harbour, a geological formation (Table Mountain and its associated chain) that protects, and nurtures it with water to feed numerous freshwater streams and rivers. Around is a great deal of fertile land for agriculture, pastoralism and hunting, while the seas, warm on one side of the Cape Peninsula and cold on the other, team with fish. Almost at the southern tip of Africa, it made a convenient stopping off point in epic sea journeys between Europe and Asia.

Its attractions in respect of land and strategic location on sea routes set up a tense relationship between different social groups that became a cauldron for South Africa’s fraught history. The First Nations Centre, a small (350sqm) building by Noero Architects, on what is now a large commercial development but whose site has a piquant history, is a tool to uncover that culture and its significance to the present, and in the words of First Nations writer Patrick Mellet, to ‘decolonise’ the land and its history.

Evening view of the site, with both sentinels visible in the ecological corridor. Photo: Paris Brummer

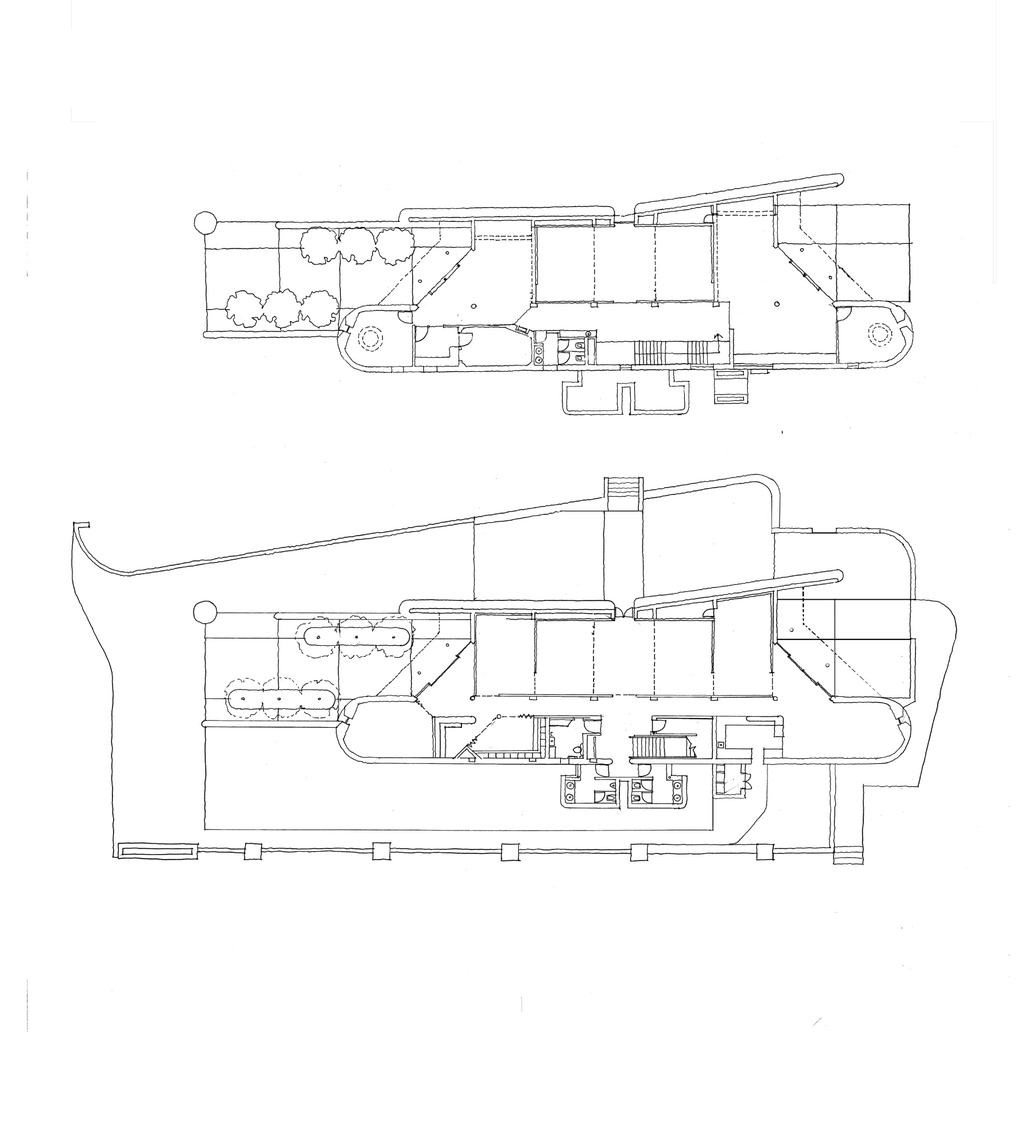

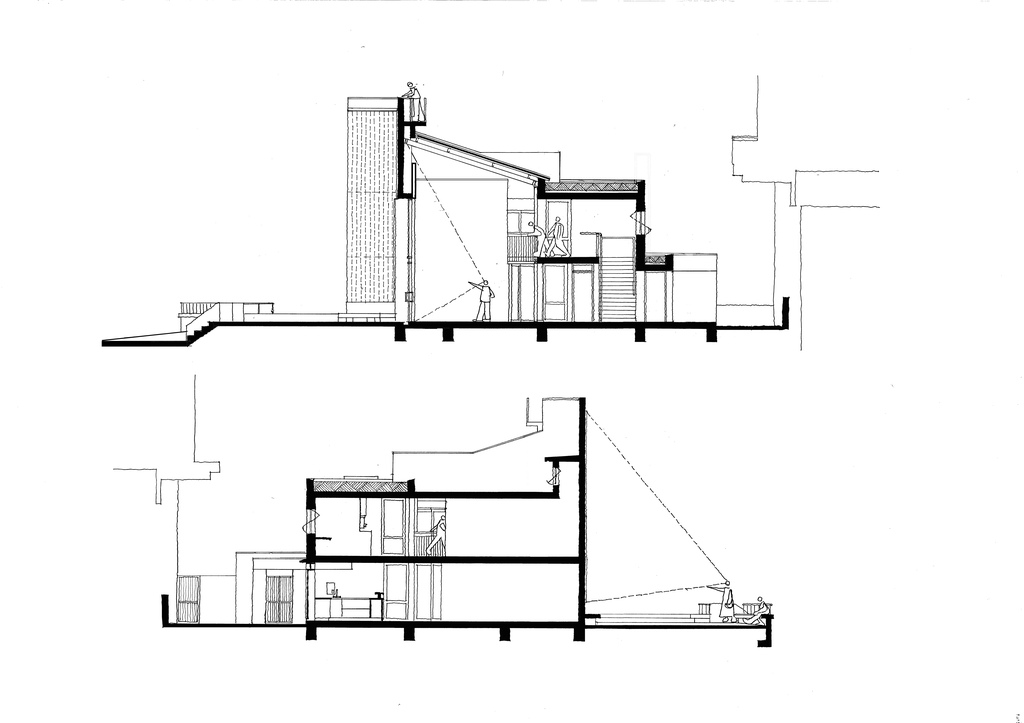

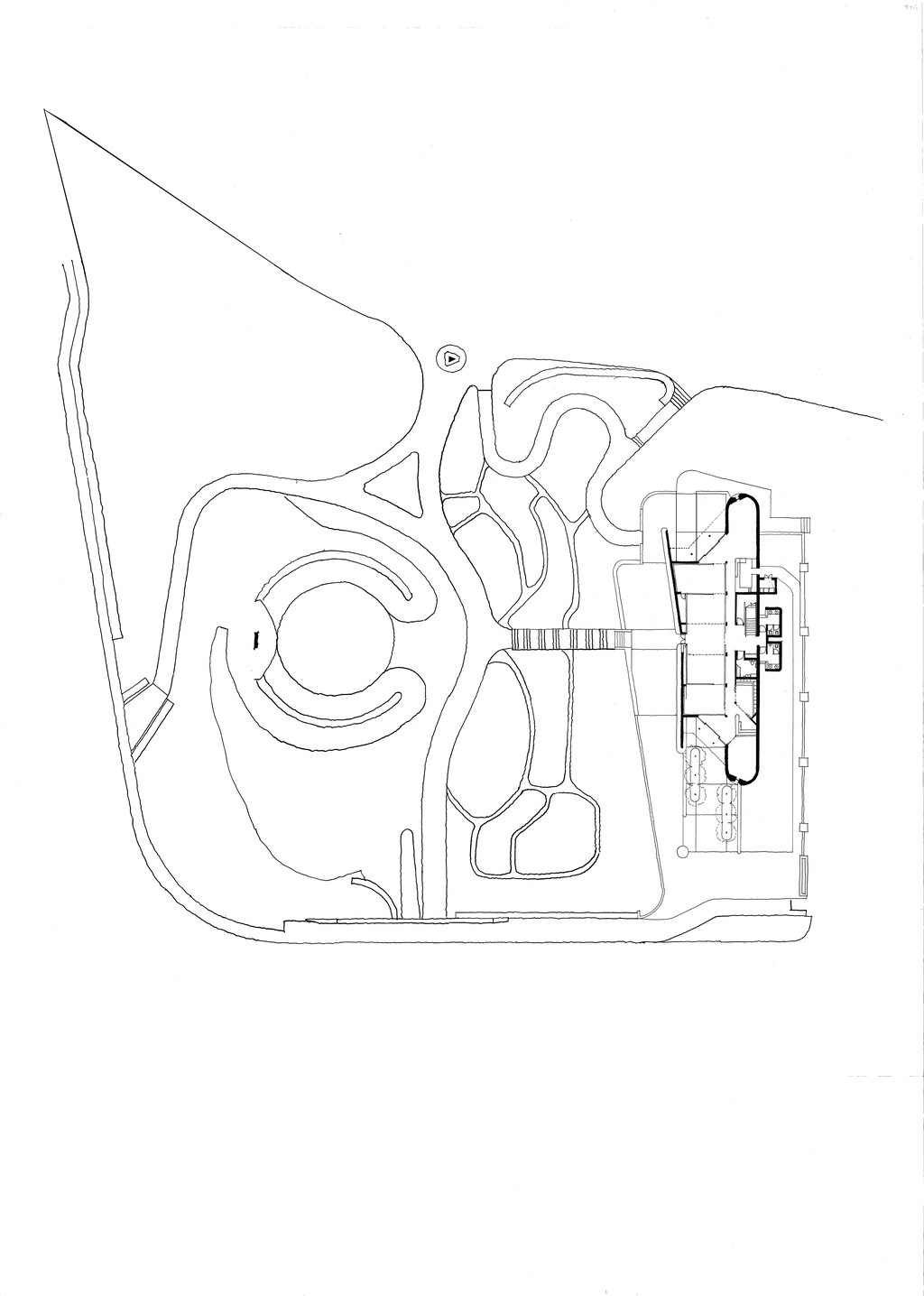

The building is, in common with much of Jo Noero’s work, a simple but rich composition, consisting of a long oblong with two semi-circular ends (containing administrative offices and meeting rooms), and a front wall detached from the oblong. Between the two forms is a top-lit gallery space which will have a display on First Nations culture and history, as well as host events on the subject. In effect reminiscent of the ‘Cape Dutch’ houses, with their low-lying white wings expanding across farmland in front of dramatic mountains, the wall is slightly kinked to respond to significant features in the landscape; laser-cut and printed onto it is a series of images of famous First Nations people.

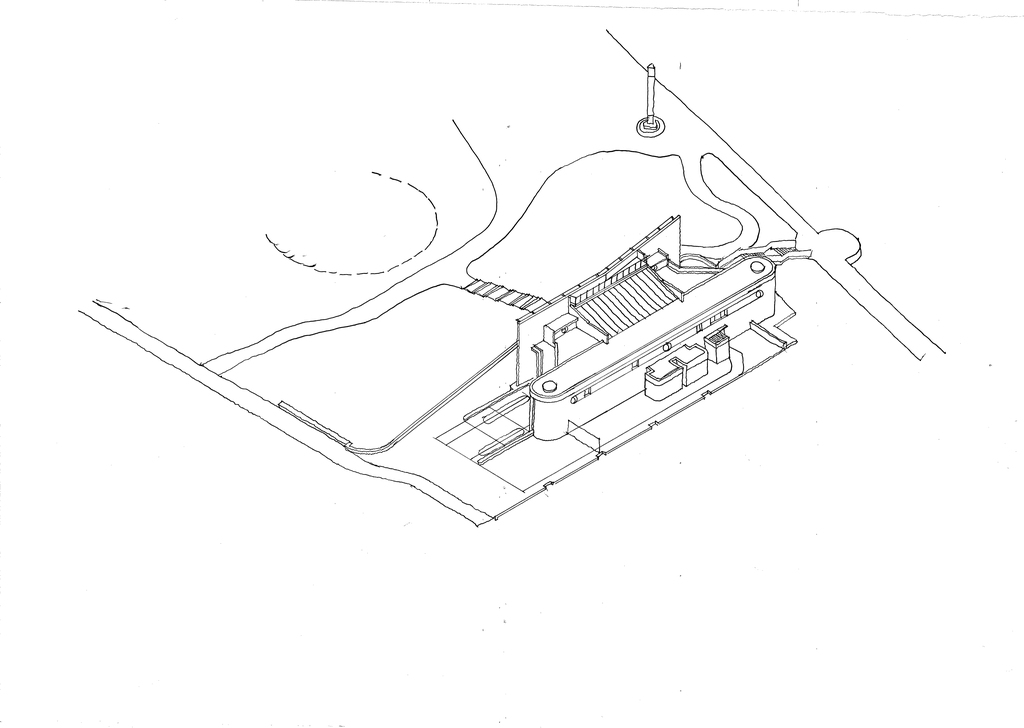

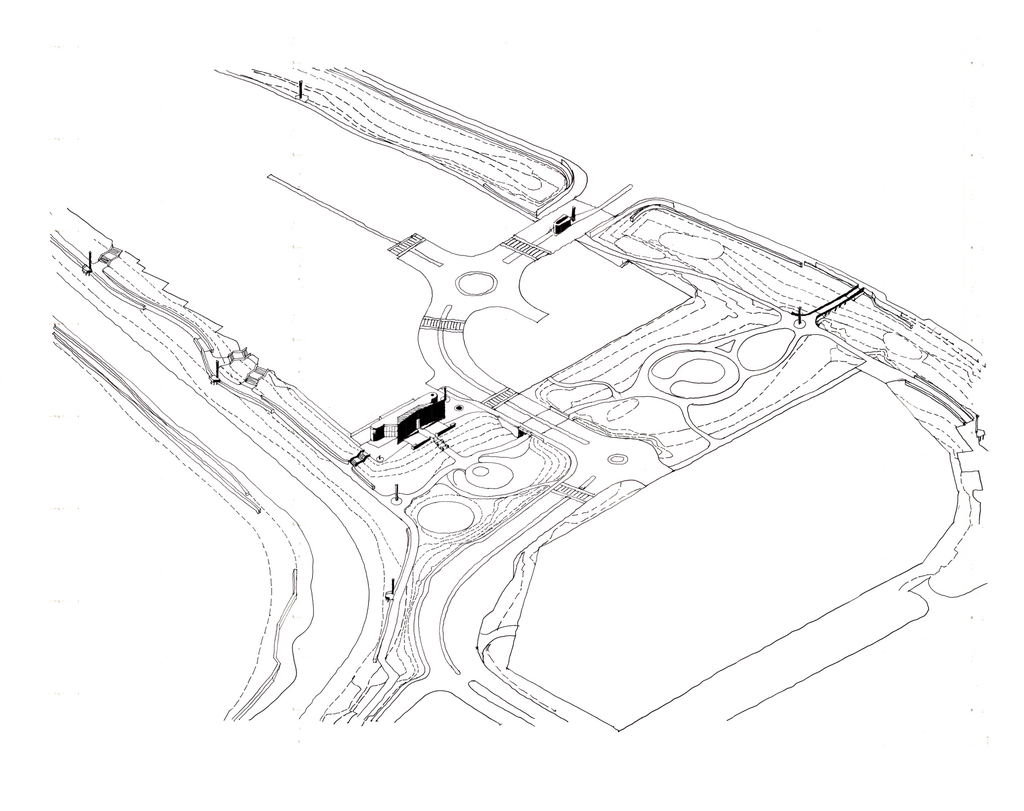

Axonometric

This follows the intention of the centre’s driving force, Chief Zenzile. A man whose wiry physique suggests an inner toughness, he is an intellectual, poet and former member of Desmond Tutu’s Truth and Reconciliation Committee, who spent many years in exile. He sees the building as an opportunity to give First Nations culture the status it deserves.

Ground and first floor plans

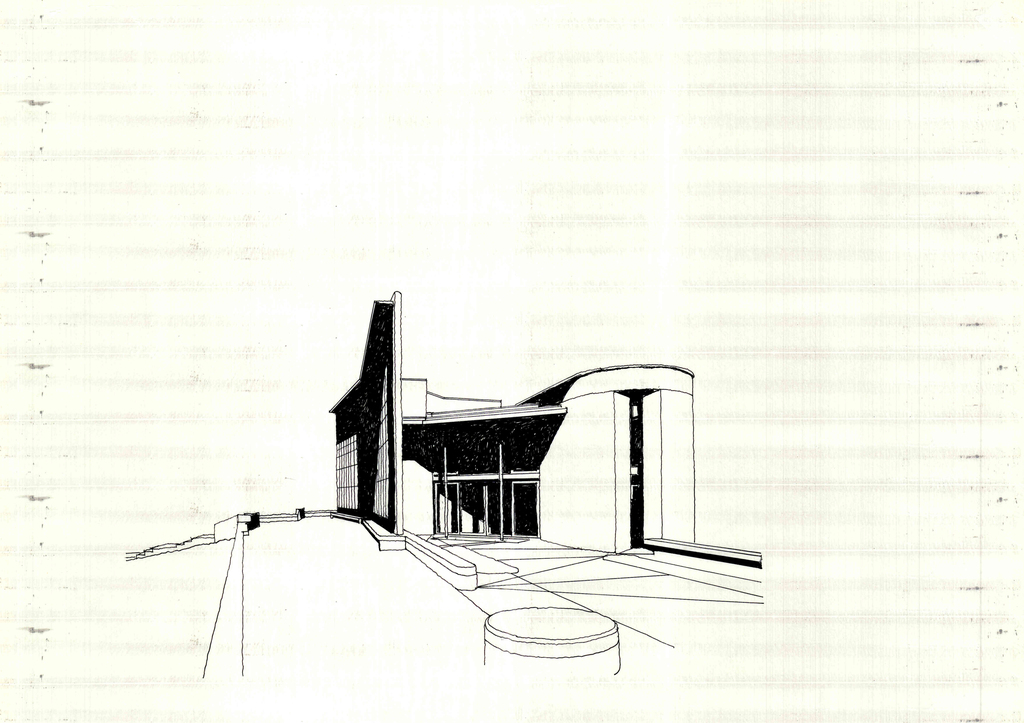

The project stems from a collaboration between a developer and the First Nations collective. Originally, the developer offered the collective 350sqm of space within a shopping centre, as if it were a retailer. Zenzile fought hard and won a separate building, with Noero as architect, in which they sought to exploit all the possibilities they could find to give it some prominence. The detached wall acts almost the porticos and domes of Santa Maria in Montesanto and Santa Maria dei Miracoli, the twin churches in Rome’s Piazza del Popolo which form the thin end of wedges of urban fabric between the Via Babuino, the Via del Corso and the Via dei Ripietta, giving the illusion to visitors entering the city through the Porta del Popolo, that the city is entirely comprised of churches.

Perspective from east, showing main entrance. The wall is almost a sign board.

Here, the illusion is not quite so complete, but despite its smaller scale, it stands up well against is commercial behemoth neighbours.

Cross sections. The heights are carefully considered both to give the building prominence and to allow views from the office building behind

This claim for first nations status needs little explanation. The First Nations people are the aboriginal inhabitants, compromising the Khoisan, pastoralists and hunter gatherers, who occupied the land for aeons before Europeans set eyes on it in the 15th century, and Black Africans who started to impinge on the territory from the north and the east around the same time. Under the pernicious Apartheid system of classification, they were termed ‘coloured’, which generally referred to those of mixed race. Zenzile points out how damaging this was, as it denied the possibility of the First Nations having a unique and coherent culture and history. Reclaiming and proclaiming this status, and its relevance to modern society, is the centre’s main goal.

Images on the wall drawn by Jo Noero, laser cut and printed on aluminium panels, showing prominent first nations people past and present

Long before its supposed foundation as the first permanent European settlement in what is now South Africa, the southern part of the continent was a rich cradle for evolution. It has fantastic flora as the Cape Peninsula is reputed to have more native plant species than the whole of Great Britain. Just up the west coast from Cape Town is a marvellously rich deposit of animal fossils, made from carcasses washed towards the sea from rivers created by seasonal rains and trapped by a sandbar. Here you can see proto elephants, giraffes and numerous other creatures. Now celebrated in a visitors’ centre and museum also designed by Jo Noero, its director Pippa Haarhoff explained that its most recent finds date from about four million years ago, just before humanoids started to appear, though they had found about three items that may be early human teeth. Compared to the richness of the other animal finds, this is insignificant.

The west end of the building, showing the wall, terrace and planting with anonymous office blocks around it. Photo: Paris Brummer

Even more important is the area’s role in human evolution. Recent scholarship (eg John S Compton, Human Origins: how Diet, Climate, and Landscape Shaped Us (Earthspun Books, 2016) has shown that southern Africa was one of several sites where more or less independently early modern humans began to emerge. Momentous changes in climate seem to have had a strong bearing on evolution, for instance when a cold spell (detectable in ice-cap analysis) caused the polar ice caps to grow and sea levels to fall. Early humans had easy access to the seashore and its abundant, protein-rich food. This seems to coincide with the evolution of bipedalism and large brains. When the climate heated up again, sea levels rose, not just denying access to the foreshore but also cutting of the evolving populations from each other. In southern Africa these early modern humans developed over time into the First Nations, or Khoisan people.

The site, showing the wall (in black) and the ecological corridor in front of it, the river (to left) and outline of the Amazon building, (to the right and bottom)

Not surprisingly given this long history of occupation, the First Nations developed a close relationship with the landscape. They understood its characteristics and possibilities for nurturing habitation, and their culture, rituals and society evolved around these conditions. The new centre recalls this knowledge, with its orientation towards what is now called Signal Hill, a prominent feature in the landscape, and relationship with the water courses – between the centre and its neighbour, occupied by Amazon – the ground falls away and is treated as a flood plain, to help restore the compromised ecology of the nearby river. All around are re-introduced native plants including, in front of the centre, a medicinal garden featuring plants the First Nations peoples, forming an ‘ecological corridor’ between river and mountain. Two pylons become the sentinels of Sunrise and Sunset.

Site plan, showing the building's composition and ground floor plan, with the medicinal garden in front of it (top of image)

When Europeans began to stop off at the Cape – first Portuguese from about 1500, followed over the subsequent 150 years by Dutch and British – the Khoisan used their knowledge of the environment to control the encounters. This they did triumphantly in 1510, when they totally outwitted a Portuguese raiding party commanded by Francisco d’Almeida, forcing long-horned cattle to stampede towards the Europeans who, weighed down on soft sand by their armour could neither fight nor flee. More constructively, they provided supplies of food and timber to repair damaged ships, establishing what Melet describes as a trading point between Europeans and First Nations, with the latter in control. A small number were even invited to join the voyages and so, sometimes spending lengths of time in Asia and Europe, became familiar with European customs, habits and trading techniques. All of this bears out Zenzile’s and Mellet’s points that the First Nations had a sophisticated culture, skilfully attuned to the landscape and climate that sustained life.

View from flood plain/garden to the sunrise sentinel foreground and the edge of Table Mountain background. Photo: Dave Southwood

What disrupted that, as in so many colonised lands, was European settlement. When the Dutch decided to make a permanent settlement in 1652, they brought European concepts of land use and ownership. They were totally alien to the Khoisan, and the way they inhabited land. It also gave false justification to European claims that Khoisan cattle could legitimately be appropriated, and worse, their true owners displaced or killed at will. What had been, before settlement, a reasonably mutual beneficial interaction quickly became one of domination. From the earliest moment of European settlement, many seeds of what became Apartheid, an especially brutal system of coercion based on land division, were present, at least in latent form. Even the Dutch belief that there was little of value in the African land contributed: it caused them to suspend their capitalist instincts and practices and so meant the settlement was always short of money, leading to low-cost labourers (ie slaves) being imported from what are now Sri Lanka, Malaysia and Indonesia.

The wall. Photo: Dave Southwood

All of this makes the goals of the centre both tough and vital, at least if the noble aim of a non-racial democracy in the South African constitution are to be achieved. Noero has spent much of the last 40 years, from the most brutal period of Apartheid, through the optimism following its fall and the resigned cynicism of now struggling to achieve spatial justice through the limited means of architecture. He is not, he is quick to point out, a politician – architecture is not politics and they cannot be substituted for each other.

The gallery space. Photo: Paris Brummer

But this small building is a tool in the hands of its operators, overseen by Chief Zenzile, for engendering a consciousness of First Nations culture to a far wider audience than the First Nations themselves, and for establishing points of dialogue. Zenzile sees the buildings as an educational resource as much as an exhibition, and its bright, sunlit spaces seem suitable for both functions. Its setting within the garden and ecological corridor offers at least a moment of reflection about what this land was before it was commodified and handed over for speculative development.

Its setting in an emerging business district, with Amazon, insurance giant Ou Mutual and a shopping centre as neighbours, may sound inappropriate but is actually highly evocative. Its design responds skilfully to this setting, presenting quite literally a face to Amazon and acknowledging the quality of office space in the Ou Mutual building by keeping the admin block low enough to see over.

The building’s architecture is attuned to these symbols of modern life as much as First Nations’ culture was attuned to its setting. The challenge now, for Zenzile and his colleagues, is to define a programme to attune that culture’s contemporary iteration to modern society.

Founder Partner